- Home

- Chris Tomlinson

Tomlinson Hill Page 2

Tomlinson Hill Read online

Page 2

I tried to imagine the black Tomlinsons. Could their family have moved to Dallas, too? Were they still in the country? What an irony that would be. I had always imagined blacks to be urban and the countryside to be white. To me, rural Texas was the backwoods, a place where the sun didn’t reach the forest floor, where rednecks still grew cotton, hunted deer, gigged frogs, and fried catfish. It was the place where the Ku Klux Klan roamed the red clay roads and burned crosses at night. The country was where the bogeyman lived.

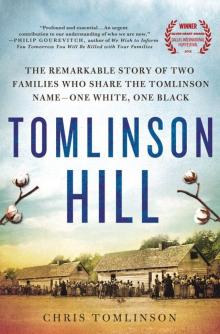

TWO TOMLINSONS

Thirty years later, I was standing on a mountain ridge near Tora Bora, covering Osama bin Laden’s last stand in Afghanistan. Fighter jets screamed through the bitterly cold winter sky, dropping laser-guided bombs on the caves where al-Qaeda had fled following the September eleventh terrorist attacks. At night, I slept in a mud hut a farmer had been using to dry peanuts. His compound was the closest shelter to the front line. The Associated Press team and a handful of other writers and photographers huddled around propane heaters to escape the mountain cold. We could hear the relentless explosions of two-thousand-pound bombs in the next valley over, but occasionally one would go astray and fall close enough to shake the walls of our shack.

We spent our days with the mujahideen at the front lines as they fought their way to reach Osama’s redoubt. At night, we sipped tea with Pashtu warlords, transmitted our stories and photographs by satellite phone, and planned for the next day.

At the same time, on the other side of the planet, a young African-American athlete worked hard to prove himself in his rookie year in the National Football League. LaDainian Tomlinson had led the NCAA in rushing his senior year at Texas Christian University, carrying the ball for 2,158 yards and scoring twenty-two touchdowns. The San Diego Chargers recognized his talent and picked him in the first round of the 2001 draft. LaDainian was one of the best running backs in the NFL, but the Chargers were one of the worst teams. He planned to change that.

On December 15, 2001, I was sitting in the sun with Afghan warlords while they used a walkie-talkie to negotiate the surrender of al-Qaeda fighters, who were decimated and demoralized by American air power. LaDainian was in Qualcomm Stadium in San Diego, being pummeled by the Oakland Raiders in a game that would end with a 6-13 loss for the Chargers.

We had never met, but we shared a common legacy. We both traced our heritage to Tomlinson Hill. And we both had traveled far from Texas to create better lives for ourselves. I was the city boy who became a foreign correspondent; he was the country boy who became a millionaire football player.

My father first told me about LaDainian in 1999 and guessed he must be a descendant of Tomlinson Hill slaves. He was right. LaDainian had spent summers with his grandparents playing in the fields where his great-grandfather had been a slave and picked cotton.

RETURNING FROM AFRICA

By 2007, I was growing weary after eleven years covering war and destruction in Africa and the Middle East. I had spent most of 2006 traveling to Somalia, getting to know the clan leaders and covering the war there, and I had lost my stomach for it. I wasn’t frightened for my life, nor was I feeling any foreboding. I had just stopped enjoying my work. I didn’t want to be surrounded by teenagers with assault rifles anymore; I didn’t want to see any more starving babies. Somalia had already been destroyed by civil war and fourteen years of anarchy. I had just witnessed another wave of violence, and I knew there was another one coming. For the first time, I felt despair.

And then Anthony died.

When I became the East Africa bureau chief, I knew one of my staff would likely die on assignment. The two bureau chiefs before me had both lost someone. But I had worked hard to train everyone to stay alive in the four war zones we covered from Nairobi. I lectured endlessly on tactics and procedures. I had felt especially responsible for Anthony Mitchell. He had been expelled from Ethiopia because of his reporting, and as a result, his wife had lost her job, their main source of income. I couldn’t do much to help him in terms of money, but I tried to give him special assignments that he enjoyed, hoping to make up for his low pay and long hours. Coming home from one of those assignments, his plane crashed nose-first into a jungle in Cameroon, leaving his two small children without a father. Telling Catherine that her husband’s plane was lost and that Anthony was likely dead tripped a circuit breaker in my heart. I’d had enough death. So a few months later, when my wife, Shalini, told me she had an interview scheduled for an exciting job in Texas, I knew fate was telling me it was time to go home.

The return to Texas was fraught with emotional land mines. Since I had left home at seventeen, I’d rarely spoken to any of my relatives. When I left for South Africa in 1993, my maternal grandmother was sure that even if I managed to escape the tribal violence, a wild animal would maul me. To people without passports and little knowledge of the world, my decision to go to Africa was unfathomable. No one ever directly asked me why I wanted to go, but neither did I offer any explanation except to say I wanted adventure. Meeting Nelson Mandela or marching through eastern Congo with Laurent Kabila’s rebel army did not impress them. They would occasionally ask me if I was making enough money, but that was about all.

After years of avoiding what Shalini called my “southern gothic” family, we moved to Austin, just a few hours’ drive away from my father. I was at a stage where I was ready to tackle whatever skeletons would leap out of the Tomlinson closet. I had made friends with Somali warlords, negotiated with drunken child soldiers, and faced down a mob of angry Rwandan refugees. How bad could my family really be? Besides, I was also going to live in my favorite city with my closest friends, whom I loved deeply.

Once we settled in Austin, I kept working for the AP on a part-time basis, making trips from Austin to Iraq and Africa on special assignments. But in between my overseas trips, I was remembering what it means to be a Texan. I saw my best friend from high school several times a week. Shalini and I would take walks on the University of Texas campus, where we had met. But I was also excited to learn the truth about my family and its legacy. I planned to go to Tomlinson Hill for the first time, and I wanted to find the black Tomlinsons.

FATHER AND SON REUNION

I decided the first step was to find those old scrapbooks. I hoped my father, Bob, would still have them and tell me more about our family. The only problem was our strained relationship. We rarely called each other on the phone. I thought maybe this would be a chance to bridge the gap.

Bob had the scrapbooks tucked away in a rented storage locker, along with his favorite bowling balls. Most of his life had been spent in bowling alleys, in one capacity or another. In the early 1980s, he started collecting cameras, and that became a part-time business. Now retired, he supplemented his Social Security check by trolling garage sales, buying old cameras for pennies and then selling them for dollars on eBay.

I drove to his home in McKinney, north of Dallas, and parked in front of the small brick house he shared with his third wife. I knocked on the hollow steel door, causing a startling amount of noise. I heard a muffled voice inside shout “Come in.” When I walked inside, Dad was at a table, which was covered with haphazardly stacked cardboard boxes, bubble wrap, plastic bags, a few screwdrivers, and four old cameras. Despite a recent bout of colon cancer that took forty pounds off his frame, he was obese again and his breathing was labored. He complained about allergies, and I could see why. The house had not been properly cleaned in years. The royal blue carpet was blotted with large stains that turned it black in places. Pet food was strewn around the house and a cat was perched on a side table next to a water bowl. A deaf and blind seventeen-year-old dog of indeterminable breed sniffed around the clutter. Allergic to animal hair since childhood, I had taken two antihistamine tablets in the car, but the smell of animals and mildew made me wonder if the pills would do any good.

On the right-hand corner of the dining table, Dad had cleared a spot, and a scrapbook was open before him. He had pulled out some loose newspaper clippings

and set them aside. “I’ve been going through this stuff to see what you might need,” he said, with no acknowledgment that we hadn’t seen each other in four years. He was being the smooth bowling ball salesman of my youth, living up to my friends’ nickname for him: “Smilin’ Bob.”

The scrapbook had a red leather cover, but the binding had disintegrated long ago. Someone had glued the closely trimmed newspaper articles to the pages in a way that made use of every square inch. Most of the stories were from the early 1900s. The majority of the clips were in English, but there were also a good number of German clippings. I had learned German in school and in the army, but when my father asked me to read some of the articles, I discovered they were from a local Dallas newspaper that published its articles in an archaic form of Swiss German. I could understand some of what was written, but most parts left me flummoxed.

“This scrapbook was kept by my grandmother on the Fretz side,” Dad explained. “I’m not sure who began it, but maybe my great-grandmother, judging by the age of the clippings.”

The vast majority of the stories were about the Fretz family and the Swiss German community in Dallas. Emil A. Fretz, my great-grandfather, had founded the Dallas Parks Board. On the day the Marsalis Dallas Zoo opened, a photo of Emil’s daughter Mary—my grandmother—was on the front page of the Dallas Morning News. She was cuddling a baby cheetah.

“The smartest thing your grandfather ever did was marry your grandmother, because the Fretzes were a wealthy family,” Dad said. “She is largely the reason he was able to retire at fifty.”

After my grandparents married in 1926, the scrapbook’s breadth expanded to include the Tomlinsons. The entries were mostly obituaries or family announcements clipped from the Dallas Morning News and other newspapers. Unlike most of the Fretz articles, the Tomlinson clippings were not glued in; someone had dropped them inside the back cover.

These carefully folded pieces of newsprint, some held together with straight pins, had once provided the earliest knowledge of my family history. They had launched my curiosity and imagination. But now that I saw these clippings, they were far fewer and shorter than I remembered. There were just eleven articles, eight of them obituaries. One was my grandparent’s wedding announcement, another a story about a fiftieth wedding anniversary, and the last was a story about a bridge collapse that had killed a cousin of my great-grandfather Robert Edward Lee Tomlinson.

I also discovered the fallibility of an eight-year-old’s memory. I had conflated my great-grandfather’s life with that of his brother Eldridge Alexander Tomlinson. Eldridge had been the Texas Ranger and cowboy, while R.E.L. had been a farmer, a real estate agent, and a school-teacher.

Trained in the art of teaching, R. E. L. Tomlinson took his place as chief pedagogue at Busby School where the Blue Back Speller and Friday afternoon Spelling Matches were the vogue. Mr. Tomlinson taught the principles of the Bible as well as fundamentals of good citizenship.1

This same story revealed other forgotten details about Tomlinson Hill.

The double wedding of R. E. L. Tomlinson and Frank M. Stallworth to the popular Bettie and Billah Etheridge twins December 23, 1891 was the social event of the season. Old Beulah Church was packed with folks from all over the county to witness the nuptial ceremony performed by the popular Baptist preacher Rev. J. R. M. N. Touchstone.… Following the wedding an old fashioned In-Fare and recreation was enjoyed by the guests. Tables groaned under the weight of fried and baked chicken and all the trimmings. The festivities even followed the two couples to Marlin, where they made their home.

As a child, I had grasped for evidence of Texan aristocracy. Reading R.E.L.’s obituary as a child had given me pride in my southern heritage, but now the same words made me cringe. In an obituary entitled “Beloved Pioneer and Leader Expires Tuesday,” the language was too easy to decipher:

He was born at Tomlinson Hill Jan. 25, 1862 son of James K. Tomlinson and Sarah Jemima Stallworth Tomlinson, at a time when the star of the Confederate States of America shone in its greatest brilliance. Of a great family of Southerners, with typical devotion to the cause and its leader the young son born during the war, was named after the famous Confederate commander-in-chief.2

Recognizing these southern dog whistles as an adult, I knew that my eight-year-old self would likely be disappointed by what I might find as I researched my family. But the investigative reporter in me was even more intrigued.

The obituaries told me that R.E.L.’s father-in-law, W. G. Etheridge, was a well-educated Unionist who had spoken out against slavery and opposed Texas secession. When the Civil War began, Etheridge fled to the North, but afterward he returned to Falls County and served as sheriff from 1875 to 1876 and was elected to the state legislature in 1882.3 I wondered what Etheridge would have thought about the fact his daughter was marrying into a slaveholding family that supported the Confederacy. I wondered which legacy would have a stronger influence on my family.

Growing up in Texas, I had known many racists, and I understood something of their netherworld. While visiting my mother’s parents in another part of East Texas, I had heard Baptist preachers claim that black skin was the “mark of Cain.” God’s curse, they argued, justified segregation. I listened to the county constable and my maternal grandfather talk about those “damned niggers” who lived across the river in Coffee City. I always knew when white men were talking about black men, because it was the only time they referred to an adult as a “boy.” Unless they were talking about a “good ol’ boy,” which meant the man was white and “dependable.” A “boy” could never be forgiven, while a “good ol’ boy” could do no wrong.

I remember going to a pool party when I was thirteen and seeing how the wealthy white family that owned the home became annoyed because the school required the parents to invite their daughter’s African-American classmates. My classmate complained that her parents would have to drain the pool afterward because of the “oils” they imagined the African-American kids would leave behind.

None of these white people would have dared reveal his or her true feelings in “mixed company.” Most would sincerely have denied they were racist. Instead, they would have argued they were realistic. I knew their attitudes were wrong, but I never spoke up. I either felt outnumbered or thought that my protests wouldn’t make a difference. I came to accept this was how most of my white friends behaved.

R.E.L. had died when Bob was only two, so he had no memory of his grandfather, nor did he know anything about James, his great-grandfather. The only thing he possessed that was linked to James was a small buckskin wallet with white stitching. The wallet was trifold, with a leather strap used to hold it closed. There were a few handwritten markings on the outside, but they were too faded to make out. But when I opened it, there was another flap over a change purse with three pockets. Using a fountain pen, someone had written in cursive script across the inside cover, “This book is an old heirloom.” Across the closure for the change purse, in the same handwriting, was written “R. E. L. Tomlinson.” Below that, on the purse itself, someone had written “R. E. L. Tomlinson Marlin, Tex. July 15, 1883.” Under the flap of the change purse, the same person had written, “J. K. Tomlinson 1850 Ala.” There were a few coins inside, including a nineteenth-century German ten pfennig piece and a buffalo nickel. We guessed that the wallet must have belonged to James K. Tomlinson, who moved to Texas from Alabama. R.E.L. was only four when his father died in 1865, so it appears that when R.E.L. turned twenty-one, his brothers gave him the wallet as a memento of the father he’d never known. R. E. L. had decided to make sure everyone knew the wallet’s provenance.

Dad said his father, Tommy, born in 1901, rarely talked about the family’s history. “He had the stock line that we treated our slaves so good that they kept the Tomlinson name after they were freed,” he told me. “But that might not be the reason they kept the name.”

My father then produced R.E.L.’s teaching certificates from the Sam Houston Normal Institute in

Huntsville. The first was dated June 10, 1886, and the second was from May 31, 1888. This was how he had become the chief pedagogue. But R.E.L. had started out at the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas in 1881, where he received a military education.

My father said Tommy talked about R.E.L. only in fragments. “R. E. L. Tomlinson had done some farming, and from what my Dad said, there were one too many floods on the Brazos,” Bob recalled. “The second or third time it happened, that finished him off.” “He was pretty prominent, but how prominent do you have to be in a town of five thousand?” Bob said. “Although Marlin was a pretty rockin’ town back then.”

In the early twentieth century, Marlin was known for its hot springs, and it is still called “the Official Mineral Water City of Texas.” Visitors came from across the state to “take the waters,” and it was a popular resort destination. Bob said his memories of visiting Marlin, all before he turned ten, were few but vivid. He said his grandmother lived in a wood-framed house with a big porch near the center of town.

“I do remember walking from their house down to the square, and there was a fire station down there. They still had an old horse-drawn fire truck,” Dad said. “They weren’t using it, but it was still there.”

Bob said that reflection was not in Tommy’s temperament, nor was Marlin dear to his heart. “He graduated from A&M in 1923 and never looked back. He moved straight to Dallas,” Dad explained. “He didn’t worry about the past; he was a builder. He wanted to put new stuff up. It if meant tearing down the [family’s] Liberty Street house to put in a parking lot to serve a building he had built for another company next door, no problem.”

Unlike his father, Bob holds on to history like a precious gem, in particular Dallas’s history. He knows the stories of the city’s inner neighborhoods and he laments the loss of landmarks from his childhood. He talks about the old Dr Pepper headquarters on Mockingbird Lane and how angry he was when the historic clock tower was accidentally destroyed during the construction of new condominiums. He told me stories about the Fretz family going back three generations, but he claimed to know little about Tomlinson history, and, frankly, he didn’t seem to have much interest in it. He said he had tried to go to Tomlinson Hill only once, but he got lost on the back roads and couldn’t find anyone who knew where it was. Whenever he spoke about his father, he would take a quick gasp of breath and then his voice would harden.

Tomlinson Hill

Tomlinson Hill